-

By Derek Duckworth

By Derek Duckworth

- October 21, 2025

- 0 Comments

- Blog

Living and Learning in Chat Rooms – What Kids Taught Each Other in Habbo Hotel

At the height of the early‑2000s moral panic, British tabloids ran headlines warning of “predators in chatrooms” and parents pictured anonymous strangers lurking behind every screen. In a small London cybercafé, however, a different scene was unfolding: groups of 10–13‑year‑olds trading tips, trying out new identities, and teaching one another how the virtual world worked.

Between 2001 and 2002, researchers Rebekah Willett and Julian Sefton‑Green decided to look past the fear and study that everyday practice. Their investigation of Habbo Hotel uncovered not only risks but also rich examples of informal learning online peer mentoring, language innovation, and identity play showing a surprising way kids were learning digital skills from each other, not just from teachers or manuals.

The Study Behind the Research

The research that first mapped informal learning patterns in chatroom spaces was carried out in London between 2001 and 2002 as part of a project called “Shared Spaces – Informal Learning of Digital Cultures.” Led by Rebekah Willett and Julian Sefton‑Green, the team worked with a sample of 10–13‑year‑old girls who used HabboHotel.com, a then‑popular virtual world where avatars, decorated rooms, and social interaction shaped everyday activity.

Methods combined direct observation, audio‑screen recordings, and short interviews conducted in a supervised cybercafé setting provided by WAC Performing Arts & Media College. The researchers aimed to answer practical questions: How do young people acquire digital skills together? How do social norms form in a mediated space? How does the interface itself support or limit learning? Exact session counts and total observation hours are not always reported in secondary summaries; where available we will flag precise figures or point to the original study for full methodology details.

This study’s timing was crucial. In 2001–2002, mainstream social media and game platforms were still emerging, which meant researchers observed learning processes as they developed rather than after norms had already solidified. That made the work a valuable early window into digital learning: it captured how children discovered shortcuts, negotiated social rules, and taught each other before those practices were codified in later platforms.

At the same time, the study had clear limitations that should temper broad claims. The sample focused on girls at a single London site in a supervised setting, so findings may not generalize to boys, other age groups, or unsupervised home use. The researchers acknowledged these constraints and framed their conclusions as an exploratory contribution to how informal learning and digital learning practices emerge in peer networks.

For readers interested in the full research methods and data, consult the original study and project reports (see bibliography or the methodology appendix where available). The study remains an important early example of how social media‑style interactions and design choices shape what and how young people learn online.

The Chatroom as a Classroom

At its clearest, the Habbo Hotel study shows informal learning as a multi‑channel process where the product (the platform) and the people (peers) teach at the same time. In other words, kids learned not by reading manuals or listening to teachers, but by interacting with an interface designed for exploration and with other users who modeled and corrected behaviour in real time.

Children don’t read manuals on how to chat — the software itself teaches them.

Researchers summarized this process in four overlapping channels (see figure caption):

- Watching peers navigate the space and copying successful moves

- Imitating on‑screen actions and locations (e.g., following someone into a popular room)

- Trial‑and‑error experimentation — trying buttons, furniture, and chat features to see what happens

- Reading interface cues and prompts (labels like “Add friend,” “Send message,” or “Room rules”) that scaffold next steps

Consider a short vignette recorded by observers: a newcomer fumbling with the chat box types “hi” and receives the reply “try /shout to get attention” she tries the command, sees more responses, and adopts the behavior. Within minutes she has learned a new affordance, not because an adult taught her, but because the interface and peers made the learning visible and rewarding.

The study uses the term “scaffolded” to describe how Habbo’s design layered simple actions into larger practices: small prompts and visible examples built up into competence over repeated sessions. That scaffold — the combination of interface affordances, peer help, and opportunity to practice with low cost for error produced complex digital literacies: managing identity, negotiating social rules, and using platform tools effectively.

Unlike classroom assessment, this was an emergent, practice‑based form of learning: users acquired skills through meaningful activities (decorating rooms, organizing role plays, applying for virtual jobs) and through conversation about what worked. For designers and educators, the takeaway is direct: platform design and community dynamics form part of the teaching system change one and you change what gets learned.

Join the Conversation

Jump into our main chat room to meet others, share ideas, and see informal learning in action today.

Enter Main Chat RoomPeer Tutoring: Helena the "Teacher"

One of the clearest examples of informal learning in the study was a recurring mentorship between two participants the researchers call Helena and Natalie (names are treated as pseudonyms in the published work). Helena, a confident and experienced user, stepped into a teacher‑like role without any formal authority: she demonstrated features, corrected mistakes, and translated platform conventions into plain conversation.

Helena’s lessons were practical and situational. The study records her showing Natalie how to:

- Use the “shout” command to make messages visible across a room

- Spot and apply for virtual “jobs” that gave status or rewards

- Recognize common scams and avoid risky exchanges

- Navigate between rooms and social spaces efficiently

The interaction style mattered as much as the content. Rather than saying “Do this,” Helena used casual, low‑pressure language: “Try shouting — it gets more people to see you” or “If someone asks for credits, don’t send them.” The researchers transcribed short exchanges where Helena modeled a step, Natalie tried it, and the group responded a micro‑cycle of demonstration, trial, and social feedback.

Evidence in the field notes suggests these quick cycles led to measurable uptake. Natalie repeatedly adopted Helena’s suggestions (for example, correctly using shout to gather attention within a few attempts), and other users began to echo Helena’s phrasing and tips. That pattern shows how peer tutoring propagated skills across the community without formal instruction or curriculum.

Compared with classroom teaching, Helena’s approach had distinctive advantages: it was immediate, contextualized, and emotionally supportive. Instead of a teacher saying “Click here” or issuing a directive, Helena embedded social norms (“I don’t like when people do that”) alongside technical tips, so Natalie learned both how to use tools and what behaviours were acceptable.

There are limits to generalizing from one pair: the study does not always report exact session counts for Helena and Natalie, and the supervised setting may have influenced behaviour. Still, their exchange is a strong example of how informal learning and social media‑style peer support function in practice a pattern replicated in many other groups observed by the researchers.

Helena’s mentorship illustrates one form of learning in Habbo Hotel. The platform also fostered language innovation and identity experimentation modes of learning that were less visible to adults but equally powerful.

Playing and Learning: The Culture of Chat

Play was not decoration in Habbo Hotel it was the engine of learning. The researchers identified three overlapping modes where play created opportunities for informal learning: language development, identity experimentation, and managed risk‑taking. Each mode produced distinct skills and social knowledge, and all three operated simultaneously in everyday chat activity.

Learning Language through Play

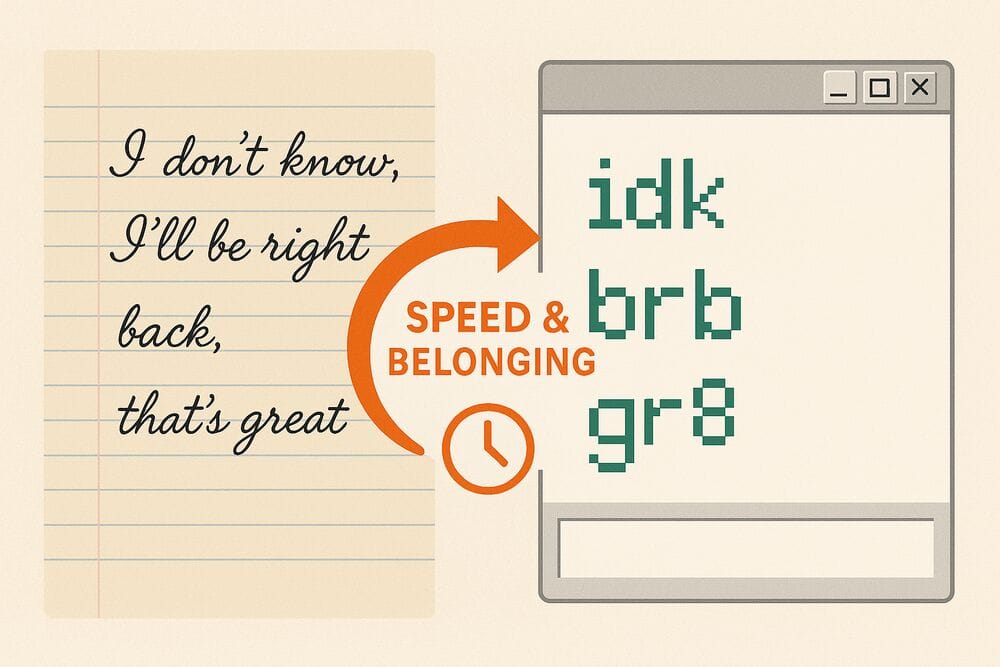

Chat language in Habbo was a living code: shorthand, phonetic spellings, and emoticons emerged because speed and visibility mattered. Common abbreviations (u, btw, gr8) and compressed grammar let kids keep up with rapid conversation — and mastery of that code signalled belonging. The researchers describe this as a new kind of literacy that combined elements of writing and speech and was learned through social interaction rather than classroom drills.

| Formal | Chat | Why it matters |

| I don’t know | idk | Faster typing; social fluency |

| That’s great | gr8 | Economy of expression; identity badge |

| I’m coming | brb | Signal coordination in shared activity |

Researchers recorded micro‑interactions where newcomers were corrected or coached by peers: a new user types “I don’t know” and a more experienced participant replies, “just say idk it’s faster.” Within a few sessions many newcomers adopted core terms; where precise counts are unavailable, observers note that core slang spread within hours or across a few visits. The developmental payoff: children practiced audience awareness, concise expression, and code‑switching transferable skills for digital learning and social media.

Playing with Identity

Avatars, clothes, skin tone and accessories became tools for experimenting with self‑presentation. The study documents participants changing outfits and looks frequently in one observational note a participant changed her avatar’s skin color and hairstyle multiple times in a single session to see different social reactions. These experiments taught aesthetic judgment, audience reading, and social risk assessment in ways that ordinary school environments rarely allow.

Identity play delivered more than surface fun: it trained students in impression management (how choices affect reputation), in empathy (testing how others respond), and in resilience (trying a new persona and coping with rejection). Because consequences were usually low — a temporary avatar change could be reversed — children could take social risks, learn from feedback, and refine their social strategies. That process builds competencies useful for online learning communities and creative digital practices.

Playing with Risk and Taboo

The researchers observed conversations that touched on age‑appropriate risky or taboo topics crushes, flirting, family friction, and occasional mild swearing subjects children often test in private. Rather than labelling these talks as simply problematic, the report frames them as developmental work: kids were negotiating boundaries, testing responses, and practicing how to manage sensitive interactions.

Observers recorded common patterns of peer regulation: when one user persisted with unwelcome romantic attention, others often intervened by ignoring the instigator and then explicitly telling them to “stop being creepy.” In other cases, group members corrected or redirected conversations that crossed agreed norms. These episodes show how communities develop enforcement practices: social correction, exclusion, or public shaming were the group’s informal sanctions a form of community‑led moderation that taught newcomers the local rules.

Importantly, the study emphasises context and supervision: most interactions remained age‑appropriate, and researchers conducted observations in a supervised setting, reducing the likelihood of serious harm. The developmental value lies in low‑stakes rehearsal: children tried out language and scenarios they might later face offline, learning social judgments and emotional regulation in the relative safety of a mediated environment.

Taken together, these three modes show how informal learning online is deeply social, practice‑based, and embedded in everyday activities. Language, identity, and boundary testing were not incidental — they were the content of learning. For educators and platform designers, the takeaway is clear: systems and communities shape what children learn, so design choices and community support should enable safe experimentation and meaningful feedback rather than simply restricting activity.

For guidance on balancing exploratory learning with safety, see our chat safety resources linked elsewhere in this article.

What Informal Learning Looks Like

The Habbo Hotel observations help clarify what “learning” looks like when it happens outside classrooms: it is exploratory, collaborative, reflective, and cultural. Unlike formal education which foregrounds objectives, teachers, and assessment informal learning online is anchored in activity, social exchange, and intrinsic motivation.

Exploratory

Children learned by doing: clicking, typing, failing, and trying again. Field notes record simple experiments pushing a button to see what happens, rearranging room furniture, or testing a chat command that produced practical knowledge. Example: a participant experimenting with the “shout” command learned its reach through repeated attempts rather than instruction. So what? Exploratory practice builds procedural fluency and risk assessment without the pressure of grading.

Collaborative

Learning rarely happened in isolation. Peers guided one another in real time, offering tips, corrections, and demonstrations. Observers noted rapid horizontal spread of techniques (one user’s hack became community practice within sessions). This collaborative network acted like a living resource: knowledge circulated through conversation, imitation, and shared activities, not through a single teacher or curriculum.

Reflective

Users didn’t just act they talked about what worked. Groups paused to critique room designs, to explain why a trick failed, or to debate fairness in role plays. These meta‑conversations produced critical awareness: learners developed the language to describe affordances, to reason about consequences, and to evaluate content and behaviour key outcomes for digital learning and media literacy.

Cultural

Most learning in Habbo was embedded in culture: norms, humor, status markers, and etiquette. Mastery of chat slang, fashion choices for avatars, or acceptable flirting signalled belonging. These cultural practices transferred as knowledge about how to behave online and how to read social cues in other digital networks.

Intrinsic motivation powered all four dimensions. Children were not completing tasks for grades they were pursuing social goals (making friends, gaining status, organizing events) and creative goals (designing rooms, role playing). Observers recorded participants spending long stretches practicing a trick or rehearsing lines simply because the activity was meaningful a lightweight form of training that produced deep engagement and sustained skill development.

Where possible, the researchers added micro‑data to these categories: notes of sessions, short transcripts, and repeated observations of the same behaviours across visits. At the same time, the study’s limits must be acknowledged: the sample was small, gender‑specific, and conducted in a supervised cybercafé, so generalizing to all students or unsupervised home use is risky. These caveats do not negate the findings but help frame them as an exploratory contribution to research on informal learning and online learning environments.

Practical implications for educators and platform designers:

- Design systems that scaffold exploration with clear, low‑cost feedback (micro‑prompts, safe sandboxes) so students can learn by doing.

- Leverage peer teaching and collaborative activities as resources rather than obstacles to control.

- Create opportunities for reflection (debriefs, meta‑discussions) so learners convert practice into knowledge.

From Chatrooms to Classrooms: Why It Matters

The Habbo Hotel research highlighted a persistent gap: schools tended to teach in formal, assessed ways while children were developing valuable digital literacies informally online. That split produced two parallel learning tracks classroom education and peer‑driven online learning with little institutional recognition of how the two could complement one another.

From the study, three transferable values stand out that formal education can learn from informal learning environments:

- Autonomy: Children in Habbo directed their own learning, choosing which activities to pursue and when to ask for help a practice that builds self‑regulation and decision‑making skills.

- Self‑expression: Avatars, room design, and chat language gave multiple channels for creativity and identity work, helping students learn how presentation and audience shape communication.

- Critical awareness: Through peer discussion and trial‑and‑error, users learned to evaluate information, spot scams, and judge social behaviour core media literacy skills for the digital age.

How to adapt Habbo’s lessons in a classroom

Rather than prescribing abstract change, here are practical, tested adaptations teachers can try to bring informal learning benefits into school settings:

- Peer tutoring rotations: Set up short sessions where more advanced students mentor newcomers on a task or tool. Outcome: faster uptake and stronger social support networks.

- Sandbox projects: Create low‑stakes, open exploration labs (digital or physical) where students can experiment, fail, and iterate. Outcome: procedural fluency and intrinsic motivation.

- Micro‑prompts and affordances: Design interfaces or worksheets with stepwise cues (micro‑prompts) that scaffold discovery without overdirecting. Outcome: scaffolded independence similar to platform design.

- Structured reflection: After play or project work, run short debriefs where students describe what worked and why. Outcome: converts practice into explicit knowledge and strengthens metacognition.

These activities map directly onto existing teacher practices peer instruction, project‑based learning, formative feedback but they reframe the teacher’s role from sole knowledge source to designer of opportunities and supporter of student networks. In other words, teachers and staff can treat student communities as resources, integrating them into curriculum design rather than policing them out of the learning environment.

Broader implications: since 2002 many educational approaches (game‑based learning, peer instruction, maker education) have echoed these patterns. Schools that incorporate play, peer networks, and scaffolded exploration tend to produce better engagement and deeper skill transfer outcomes that align with workforce and civic readiness goals.

For educators seeking ready resources, consider short professional development courses on digital pedagogy, downloadable classroom briefs that translate Habbo‑style activities into lesson plans, and staff training that focuses on facilitating rather than micromanaging exploratory work.

Learn more about Online Safety Education and for teachers, look for our upcoming checklist: “Bringing Informal Learning into the Classroom” (practical activities, risks and mitigations, and assessment rubrics).

What It Says About Online Culture Today

The habits and learning dynamics the Habbo study described have not disappeared they have migrated and scaled across modern platforms. Today’s online networks such as Discord, Roblox, and Minecraft show the same mix of peer teaching, identity play, and community‑enforced norms, but on larger networks and with more complex design affordances and moderation systems.

Key continuities and lessons for today:

Peer Learning Dominates

Across platforms, peer instruction remains the fastest route to acquiring platform‑specific skills. On Discord servers or Roblox groups, a single user’s technique (a building trick, moderation shortcut, or chat convention) can spread horizontally through the community far faster than top‑down teacher or moderator messaging. That makes user networks powerful resources for informal learning.

Design Shapes Learning

Platform affordances what buttons are visible, how notifications work, what actions are rewarded continue to shape what users learn. Modern design patterns like guided tutorials, sandboxed creative modes, and visible affordances echo Habbo’s scaffolded features; they channel exploration and determine whether peers can easily demonstrate or replicate behaviours.

Safety Through Skills

Recent evidence suggests that developing users’ critical judgment is a more durable safety strategy than blanket restriction. Teaching people how to spot scams, evaluate messages, and apply community norms produces safer outcomes than simply blocking access. In practice, guided experience and scaffolded tasks build the skills users need to navigate risk.

Community Standards Emerge

Online communities still invent their own rules and enforcement methods. Whether through peer moderation on Discord, group norms in Roblox servers, or social sanctions in gaming communities, users frequently police behaviour themselves a continuation of the Habbo pattern of community‑led norm formation.

Short case: peer learning on Discord

On many Discord servers, newcomers learn server customs via pinned posts, quick onboarding channels, and live demonstrations by veteran users. A simple example: a new user asks how to use a bot command; a veteran replies with a short example, others replicate it, and the server adopts a shorthand. This microcycle (question → demonstration → imitation) mirrors the Habbo processes and shows how design (pinned messages, roles, bot responses) supports peer learning at scale.

Design checklist for platform builders

- Provide low‑cost sandboxes or demo spaces where users can experiment without consequence (supports exploratory learning).

- Expose simple, discoverable affordances (micro‑prompts, tooltips, pinned examples) so peers can teach through visible actions.

- Enable lightweight peer‑moderation roles (trusted users, mentors) to scale community enforcement while giving peers structured support.

- Offer reflection and reporting channels (debrief threads, feedback forms) so communities can discuss norms and learning outcomes.

Designers and educators should be careful not to treat Habbo and modern platforms as identical; technology, scale, and commercial incentives differ. But the study’s core insight that systems and communities jointly teach remains relevant. Platforms that balance protection with opportunities for guided exploration are most likely to foster positive learning outcomes and resilient communities.

For product teams, a practical takeaway is to build moderation and safety tools that support exploration (sandboxed tutorials, mentor roles, clear affordances) rather than only suppress behaviour. These patterns let users teach each other within safe boundaries and harness the powerful informal learning dynamics first observed in early chatrooms.

Conclusion

The Habbo Hotel study reminds us that chatrooms were never only streams of text — they were laboratories for social learning. When young people play, experiment, and teach one another, they’re practicing the same social and cognitive skills humans have always learned together: negotiating identity, testing norms, and building shared knowledge.

Far from being purely risky or frivolous, these spaces produced measurable learning outcomes: technical skills with platform tools, social competencies around etiquette and moderation, and emergent critical awareness about persuasion and scams. Those outcomes grew out of everyday activities and peer networks, not formal instruction; in that sense, informal learning can be as consequential as classroom learning for development and later digital participation.

That doesn’t mean every online space is automatically beneficial. The study’s findings are suggestive rather than universally prescriptive — contexts, supervision, and design matter. But its core lesson is robust: systems and communities together shape what is learned. Platforms that scaffold exploration, surface affordances, and enable peer support will promote better learning outcomes than ones that only restrict behaviour.

What educators, parents, and designers can do next

- Educators: Treat student networks as learning resources — run peer tutoring rotations, sandbox projects, and short reflection sessions to convert practice into explicit knowledge.

- Parents: Encourage guided exploration and dialog about online experiences rather than only imposing bans — support development of judgment and digital skills through conversation and supervised practice.

- Designers and platform teams: Build affordances that make learning visible (tutorial sandboxes, micro‑prompts, mentor roles) and tools that support community enforcement rather than relying solely on top‑down moderation.

Recommended further reading: consult the original Shared Spaces project materials and later work on digital literacies to trace how early observations in Habbo informed contemporary thinking about informal learning online and media education.

Meet People in London Chat Rooms

Connect with locals, chat about life in the capital, and make new friends from across London in our dedicated chat rooms.

Visit London Chat Rooms“At World of Chat, we're committed to creating safe, inclusive spaces for connection and learning. Learn more about our Community Standards that help make our platform a positive environment for all users.”

Key Citations

- Willett, R. & Sefton-Green, J. (2002). Living and learning in chatrooms (or does informal learning have anything to teach us?)

Education et Sociétés, 2, 57–77. - Buckingham, D. (ed.) (2007). Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. MIT Press.

- Buckingham, D., Sefton-Green, J. & Willett, R. (2003). Shared Spaces: Informal Learning and Digital Cultures. London: Institute of Education.

- Sefton-Green, J. (2004). Literature Review in Informal Learning with Technology Outside School. NESTA Futurelab.

Recommended Reading

- Buckingham, D. (2005). The Media Literacy of Children and Young People. UCL Institute of Education.

- Sefton-Green, J. (2006). Informal Learning and Digital Media. Reflections on learning beyond school.

- Pereira, D. (2019). Young people learning from digital media outside of school. EJ1201216 (ERIC Report).

- Monteiro, A. F. & Osório, A. J. (2016). Digital childhood, risks and opportunities: Why is it so important to listen to children? Children & Society.